By Arjan Schütte and Matthew Shackelford

For years, I’ve been going around saying it’s expensive to be poor. It’s the kind of quip that receives a knowing nod recognizing a dark irony. When I founded Core, I had a slide in an early, unsightly deck that said the underbanked spend approximately 17% of their income on basic stuff you and I get for free.

During the past several years, it has dawned on me that it’s not just expensive to be poor; it’s expensive to be an American. Matthew Shackelford, our fabulous summer associate, dug into the data: A majority of people are living paycheck to paycheck — and that’s before COVID! How is that possible after 11 years of unprecedented growth and record low unemployment?

The Cost of Living the American Dream

Cost of living data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics makes it pretty clear. Expenses for the median American exceed after-tax income. Basic necessities, including housing, car, food, clothing, and healthcare, account for more than 75% of income, leaving less than a quarter for discretionary spending. To say nothing of any saving, investing or shock protecting (insurance). In a world where the number of Americans with major income volatility is growing, the cost of living for middle class Americans leaves little breathing room in case of an emergency.

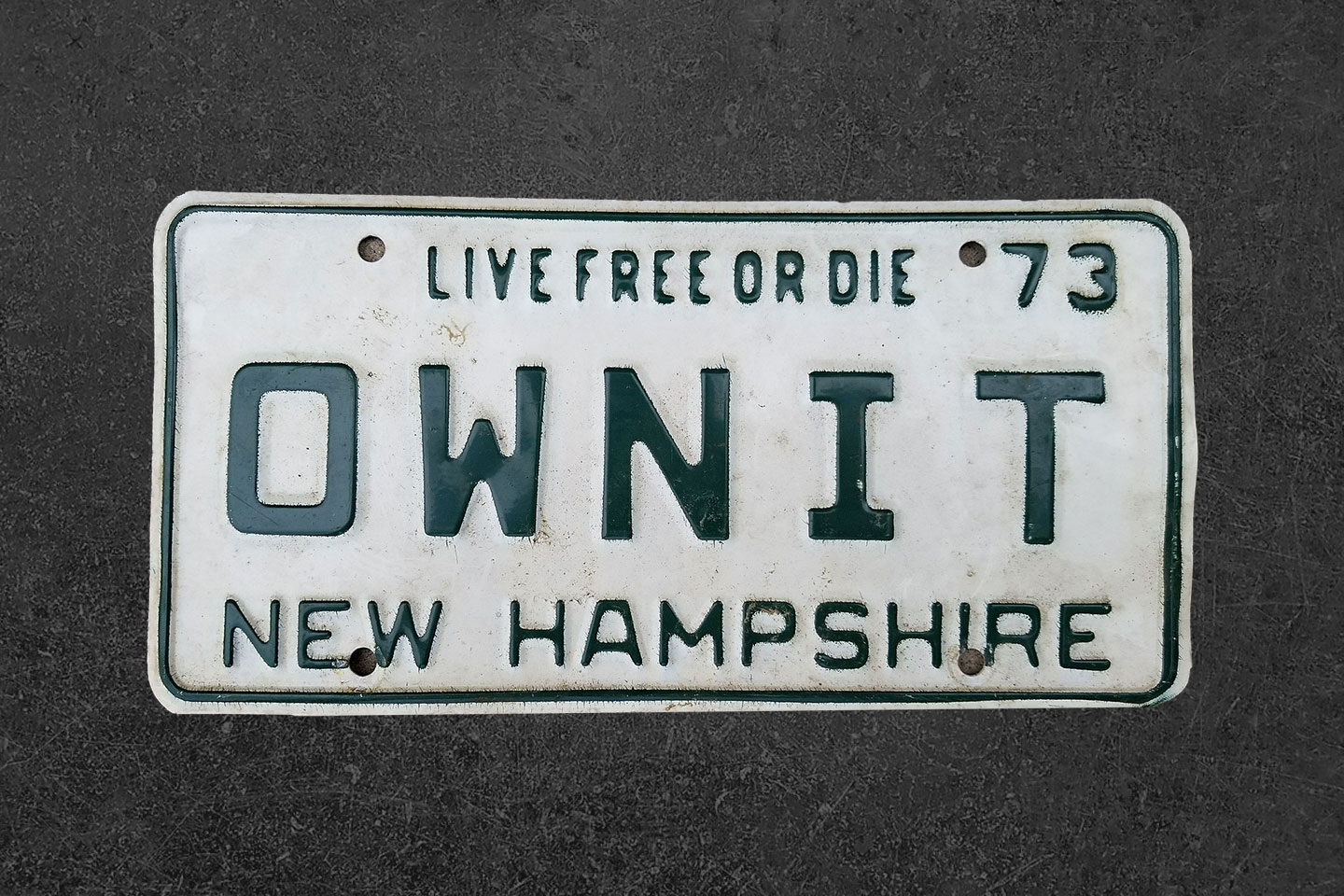

To make matters worse, the fortunes of the middle class haven’t been improving over time; in fact, they’re getting worse. Adjusted for Consumer Price Index (CPI) inflation, the purchasing power of the average American hourly wage peaked in 1973 and has largely declined or been stagnant since. But even that doesn’t tell the whole story! The prices of some of the biggest contributors to a household’s cost of living, including housing and healthcare, have increased much faster than CPI inflation. In nominal terms, housing costs have risen by 188% over the past three decades, with healthcare rising 276%, compared to just 116% as measured in CPI terms. Accounting for these accelerated price increases, average American households have lost ground in the fight to maintain a middle-class lifestyle, considering that wages have only nominally risen 135% over the same period.

Kitchen Table Domino Effect

The median American living progressively closer to the edge of affordability (or beyond it) has downstream implications beyond just an inability to purchase the car they want. It impacts people’s ability to save for retirement, invest in education, and brace against shocks.

The median American has a negative net annual savings rate. Because of this, nearly half of working-age families have nothing whatsoever saved for retirement. Furthermore, there’s a growing gap between the middle class and the wealthy as retirement accounts with smaller balances have stagnated while larger ones have grown rapidly, largely due to the withdrawal of savings to handle present-day needs as the relative cost of living has increased. It’s estimated that for every dollar that flows into 401(k)s, between 30 and 40 cents leaks out before retirement. The inability to save for retirement due to high costs is setting up the median American family for disaster later in life.

Spending on education as a percentage of income has stagnated for the average American, hovering around 2% of after-tax income for the median American over the past 10 years. Ideally, this percentage would be rising over time due to the increasing educationalization of the economy. Employment in occupations requiring average to above-average levels of preparation is expected to grow 7.9% through 2024, while employment in occupations requiring below-average preparation is projected to grow by only 5.1%. Because the cost of basic necessities is so high, middle-class families are unable to invest in education that is becoming increasingly critical to maintaining a stable, well-paying career, putting them at a permanent disadvantage over the long run.

What stands in relief in the COVID-19 era is that household financial resilience is critical, both for individuals and the economy. Sadly, the elevated costs of basic necessities render families more susceptible to volatility, triggering vicious cycles of financial instability when shocks, both global and local, occur. Spending upwards of 75% of after-tax income on the basics means that households have little room to cut back if their hours or wages get slashed. During the most recent crisis, Americans have cut back discretionary spending as far as it can go, leading the savings rate to hit 33% in April (although this is likely skewed heavily towards the upper end of the income distribution). Despite this, lower- and middle-income Americans still needed and continue to need significant external support, requiring government intervention. Even in more normal times, 35% of US consumers experience a financial distress event at some point in their lifetimes. Simply put, living increasingly close to the edge has led the median American to fall over it more frequently.

What to Do, What to do?

Fintech entrepreneurs and investors have to recognize the underlying problem that most Americans face: The rents (and vehicle expenditures and healthcare prices) are too damn high. The majority of consumers don’t need the 55” OLED TV; they need cost reduction.

There are certainly fintech startups providing necessary and valuable solutions that focus directly on the symptoms of the underlying problem. Several help people save, including Digit, Acorns and Better Mortgage. We need more! Others are tackling issues in education, such as Vemo, which provides income share agreements to expand educational access, and U-Nest, which streamlines parental 529 college savings.

But it’s also critical for investors to back companies that are facing cost reduction for the median American head on. In the housing space, PadSplit is decreasing the cost of housing by optimizing the utilization of existing apartments and houses, while in healthcare, Galileo is lowering the cost of primary care delivery through technology and capital efficiency. These startups and others have the potential to not only change the game of everyday Americans’ cost of living, but also gain significant market share and generate high returns in the process.

As fintech innovations become more embedded into verticals of the economy that represent big cost centers for everyday Americans, these will help ameliorate the structural challenges we describe and see around us. And it can’t happen without smart industrial policy to increase incomes for the majority, while keeping prices low with automation and the benefits of globalization.